Discover Iran: Great Wall of Gorgan – a Sassanid-era engineering marvel in Golestan

By Ivan Kesic

- Great Wall of Gorgan is the longest fort-lined ancient barrier between Central Europe and China, surpassing the combined length of Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall.

- Its construction in a resource-scarce steppe required a unique hydraulic system, including a canal that ran its entire length and an estimated 200 million custom-fired bricks produced from thousands of kilns.

- This colossal project, built by the Sassanid Empire in the 5th century AD, featured a sophisticated multi-layered defense with over 38 forts and hinterland campaign bases capable of housing a garrison of up to 40,000 soldiers.

Beneath the sun-baked earth of northern Iran lies a monument to the royal past and engineering genius that rivals the most famous defensive barriers of the ancient world.

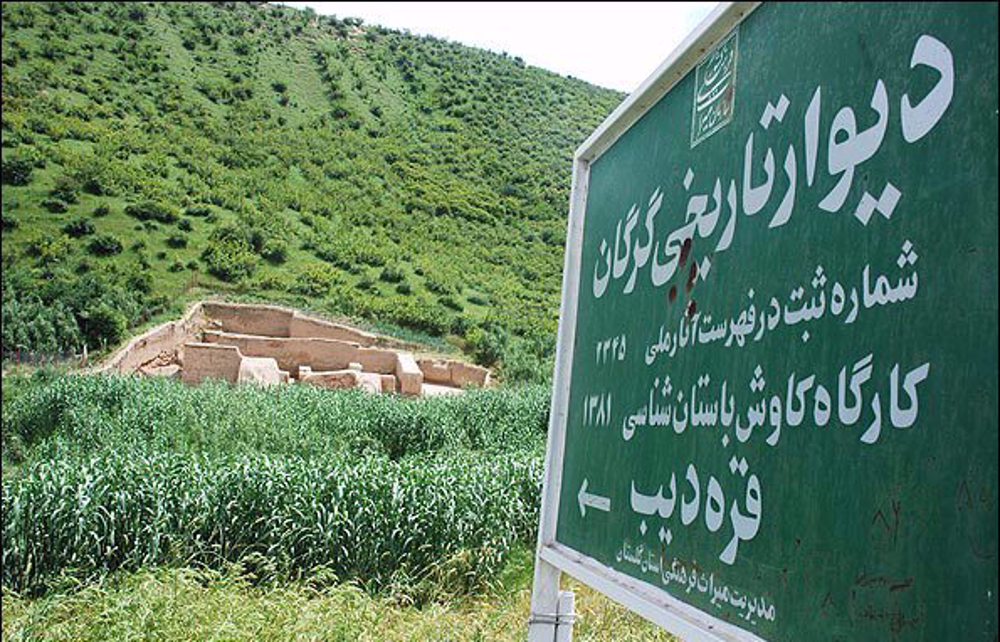

Stretching for almost 200 kilometers from the Alborz Mountains to the Caspian Sea, the Great Wall of Gorgan in the northeastern province of Golestan stands as a testament to the power and sophistication of the Sassanid Empire, a colossal undertaking that protected one of history's greatest empires from the steppe nomads of the north.

Often overshadowed by its later Chinese and more famous Roman counterparts, this formidable wall, known locally as the "Red Snake" for its distinctive fired bricks, represents a pinnacle of ancient military architecture, hydraulic engineering, and logistical organization.

Its scale is staggering, its construction techniques revolutionary for its time, and its silent, crumbling forts whisper tales of a well-organized imperial army that once guarded the prosperous heart of Iran from incursion.

It is not merely a wall but an integrated defensive system of unparalleled complexity, whose rediscovery and scientific analysis have forced a reevaluation of Sassanid capabilities and their crucial role in the geopolitical dramas of Late Antiquity.

A colossal scale in a contested landscape

The sheer physical dimensions of the Great Wall of Gorgan immediately establish its global significance. At approximately 200 kilometers in length, it is the longest fort-lined ancient barrier between Central Europe and China.

To comprehend its scale, it is longer than Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall in Britain put together and more than three times the length of the longest late Roman defensive wall built from scratch, the Anastasian Wall near Constantinople.

The wall was lined by at least 38 forts, whose combined area exceeds that of the forts on Hadrian's Wall about threefold, suggesting a massive and permanent garrison.

This defensive complex may have been part of an even larger system, potentially connecting with the shorter but similarly designed Tammisheh Wall to the west, both running from the mountains to the sea and forming a cohesive shield for the Gorgan Plain.

This plain constituted a fertile and prosperous region of the Sassanid Empire, a strategic frontier that required robust protection from northern threats, first from the Hephthalites, or White Huns, and later from the Turks.

The wall was built and occupied from the 5th to the 7th centuries AD, a decisive period that saw the demise of the Western Roman Empire.

Solving an engineering conundrum: Brick kilns and water canals

The most extraordinary aspect of the Great Wall of Gorgan in Golestan is not its length but the revolutionary engineering solutions required for its construction.

The treeless, stoneless steppe of the Gorgan Plain offered no traditional building materials. The Sassanid engineers responded to this challenge with breathtaking ambition, deciding to build the entire barrier from fired bricks.

Estimates suggest that around 200 million bricks, each weighing approximately 20 kilograms, were required. To produce this staggering quantity on-site, the builders established a veritable industrial production line along the wall's course.

Archaeological surveys have revealed the presence of brick kilns placed at remarkably close intervals, every 37 to 86 meters, amounting to a potential total of 3,000 to 7,000 kilns.

The firing of these bricks, however, presented another monumental challenge: it required a vast and reliable supply of water. The Sassanid response was a masterpiece of hydraulic engineering.

They dug a primary canal that ran alongside most of the wall's course, a channel at least 5 meters deep. This canal was fed by a complex system of supplier canals that bridged the Gorgan River via qanats, those iconic Iranian underground aqueducts.

One of these supplier canals, the Sadd-e Garkaz, survives to a length of 700 meters and a height of 20 meters, though it was originally almost a kilometer long.

The entire system, from the qanats to the main canal, had to follow a precise, constant natural gradient over more than 100 kilometers to ensure a steady flow of water for brick production and for the garrison's needs.

This achievement stands as one of the most impressive feats of survey engineering from the ancient world.

A monument exceeding the Great Pyramid

While the Great Pyramid of Giza stands as an iconic symbol of ancient achievement, the Great Wall of Gorgan represents a feat of engineering on an even grander physical scale.

Calculations based on archaeological evidence reveal a staggering truth: the volume of fired bricks used in the Sassanid wall surpasses that of the entire Great Pyramid.

To construct this northern barrier, an estimated 200 million custom-fired bricks, each measuring 40 x 40 x 10 cm, were produced, amounting to a total volume of approximately 3.2 million cubic meters.

This eclipses the Pyramid's estimated volume of 2.6 million cubic meters.

This comparison solely considers the brickwork; when the volume of the wall's associated earthworks, canals, and dozens of forts is factored in, the disparity becomes even more profound.

The Pyramid's brilliance lies in its concentrated mass and precision, but the Wall's achievement is one of decentralized, logistically breathtaking industrial production spread across 200 kilometers of frontier, requiring a sophisticated network of kilns and aqueducts simply to manufacture its core building material.

This places the Great Wall of Gorgan in a unique class as one of the most volumetrically substantial and complex construction projects of the ancient world.

Dating the Leviathan: Scientific techniques and historical context

For centuries, the origins of the Great Wall of Gorgan were shrouded in mystery and folklore, sometimes mistakenly attributed to Alexander of Macedon.

Modern scientific dating techniques have now conclusively resolved this question, firmly placing its construction within the Sassanid era.

The key to unlocking this mystery lay in the bricks themselves. Using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating, a technique that measures the last time quartz or feldspar minerals in clay were exposed to heat or sunlight, researchers analyzed bricks from the wall.

When bricks are fired in kilns, their luminescence clock is reset; from that moment, it begins ticking again as the bricks are exposed to natural background radiation.

OSL dates from bricks, combined with radiocarbon dating from associated materials, consistently point to a construction period in the 5th century AD, possibly extending into the very early 6th century.

These scientific dates align perfectly with the historical context of the Sassanid Empire's prolonged wars on its northern frontier.

Historical sources, such as the 6th-century historian Procopius, describe King Peroz gathering his forces at "Gorgo" in Hyrcania for campaigns against the Hephthalites, wars in which he ultimately lost his life in AD 484.

The Great Wall of Gorgan was thus a direct and colossal response to a very real and persistent military threat, a strategic imperative made manifest in brick and earth.

An army in residence: Forts, barracks, and campaign bases

The wall itself was merely the spine of a far more extensive military organism. The over 38 forts integrated into the barrier were not simple watchtowers but substantial military compounds.

Excavations, such as those at Fort 4, have revealed that these forts contained barracks of standardized design, pointing to a highly organized and professional Sassanid army.

The uniformity in construction suggests a central command and a systematic approach to military housing and logistics. Beyond the linear barrier itself, the defensive system extended deep into the hinterland.

Archaeologists have identified massive campaign bases, each covering approximately 40 hectares.

Within one of these bases, the remnants of a "tent city" were found – rectangular enclosures arranged in neat double rows, indicating the temporary quarters of a mobile field army that could be rapidly deployed to reinforce any threatened sector of the wall.

This multi-layered defense-in-depth, comprising a static linear barrier with a large permanent garrison backed by a mobile strategic reserve, demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of military strategy that rivals any contemporary system.

A global perspective: Gorgan Wall in world history

When placed in a global context, the Great Wall of Gorgan emerges as arguably the most sophisticated linear barrier of its time.

While the contemporary and earlier counterparts of the Great Wall of China were primarily massive earthworks, the Gorgan Wall was a complex structure of fired brick, integrated canals, and sophisticated forts.

It is longer than any of the Roman linear walls in Europe and, while shorter than the German Limes, it formed a more formidable physical obstacle.

The estimated garrison, based on the combined size of the forts, could have been as high as 30,000 to 40,000 soldiers, a force larger than that stationed on Hadrian's Wall.

This immense investment in border defense helps to explain the geographic extent and longevity of the Sassanid Empire, which at its peak stretched from Mesopotamia to the Indus Valley.

The wall protected the prosperous agricultural heartland of the Gorgan Plain, ensuring economic stability and security that allowed the empire to flourish.

Its effectiveness may have even allowed the Sassanids to concentrate their military forces elsewhere, contributing to their successful campaigns against the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th and early 7th centuries.

The Gorgan Wall is thus not an isolated monument but a key piece in the puzzle of Late Antique geopolitics, an Iranian masterpiece that shaped the destiny of empires.

The call for World Heritage

Today, the Great Wall of Gorgan survives as a distinct landscape feature, though its preservation varies. While much of the brick superstructure has been robbed over the centuries, sections still stand up to 1.5 metres high, and the earthworks, canals, and forts remain impressively visible in many areas.

The wall is particularly well-preserved in the eastern hilly landscapes, where its strategic positioning on high ground can still be appreciated.

Its outstanding universal value has been formally recognized by its placement on UNESCO's Tentative List, with Iran nominating it based on criteria that highlight its masterful engineering, its testimony to cultural exchange, its unique representation of the Sassanid era, its illumination of a pivotal historical period, and its evidence of human interaction with the environment.

The potential submergence of its western terminals by a rising Caspian Sea further adds to its significance as a record of environmental change.

The Great Wall of Gorgan is more than a relic. It is a monument that demands a rethinking of the ancient world, placing Sassanid Iran firmly at the forefront of technological and military innovation.

Its full recognition as a World Heritage Site would not only protect this irreplaceable treasure but also finally grant it its rightful place in the global narrative of human achievement.

Iran Army slams EU’s blacklisting of IRGC as ‘shameful’, ‘irresponsible’

Iran considers armies of EU states as ‘terrorist organizations’: Security chief

Sharif University scholars condemn US foreign policy as illegal, destabilizing

Pezeshkian says Iran seeks no war, vows 'decisive' response to any attack

Iran ready for both war and dialogue, ‘will not accept dictation’: FM Araghchi

Trump warns UK against enhancing China ties as PM Starmer hails reset

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Iran rejects threats, backs win-win diplomacy, Pezeshkian tells Erdogan

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website