Peruvians head to polls to choose between right-wing populist and radical leftist

Peruvians will pick a president on Sunday in an election that has bitterly divided them by class and geography, with urban and higher-income citizens preferring right-wing Keiko Fujimori while the rural poor support leftist political novice Pedro Castillo.

The new leader will need to tackle a country in crisis, suffering from recession and with the worst coronavirus death rate in the world after recording 184,000 mortalities among the 33 million population.

And after four presidents in the last three years and with seven of the last 10 of the country's leaders either having been convicted of or investigated for corruption, Peruvians will look to their next leader to bring an end to the recent turbulence.

Last November, the country cycled through three presidents in just a few days, a political crisis that sparked fierce protests and left several people dead.

Two million Peruvians have lost their jobs during the pandemic and nearly a third of the country now live in poverty, according to official figures.

Polls show the race in a statistical dead heat but with Fujimori, who had earlier trailed Castillo, pulling slightly ahead.

Now voters must decide between their polar opposite economic and political programs.

Fujimori, 46, the daughter of jailed ex-president Alberto Fujimori, is promising to maintain economic stability and pro-free market policies in the world’s second-largest copper producer, as well as to pardon her father, who was sentenced for human rights violations.

Fujimori herself spent several months in custody on corruption allegations she denies. If she wins, the criminal case against her will be halted while she leads the country.

Castillo, 51, an elementary school teacher and union leader, has galvanized support from Peru's rural poor - and scared investors – with pledges to nationalize the mining sector, a stance he later sought to take back. He has vowed to alter multinational companies’ tax regimes and wants to rewrite the country's constitution.

He is from a remote village near the town of Tacabamba, in Peru's northern Andes, which on Saturday night cheered him as he made his way back home to vote. Castillo gave brief remarks, even though political campaigning is banned in the last days before an election in Peru.

The city government installed a stage in the main square, which was filled with supporters and music. The rest of the city has been plastered with pro-Castillo banners, without a single pro-Fujimori sign to be seen.

"We're fed up with always being governed by the same people, we want Peru to change," Martha Huaman, 27, a fruit seller in Tacabamba, in the Cajamarca region where Castillo lives, told AFP.

For many in Peru this election is about the "lesser of evils."

"I don't even want to vote, neither of them deserve it, but Castillo panics me so I'm going to vote for Fujimori," said trucker Johnny Samaniego, 51, who lives in Lima.

Whoever wins will have a hard time governing as Congress is fragmented. Castillo's Free Peru is the largest single party, just ahead of Fujimori's Popular Force, but without a majority.

If Fujimori wins "it won't be easy given the mistrust her name and that of her family generates in many sectors. She'll have to quickly calm the markets and generate ways to reactivate them," political scientist Jessica Smith told AFP.

If Castillo triumphs, he'll have to "consolidate a parliamentary majority that will allow him to deliver his ambitious program," added Smith.

But in either case "it will take time to calm the waters because there's fierce polarization and an atmosphere of social conflict," analyst Luis Pasaraindico told AFP.

‘They promise everything’

Many Peruvians hold a deep mistrust of politicians following two decades in which five former presidents have been investigated or prosecuted for corruption.

Ruth Rojas, a Peruvian mother with a disabled daughter who said she lived in deep poverty, said she believed neither of the candidates’ vows.

"They promise everything until they get into government but then they forget about the poor, they just think of themselves and their own people," she told Reuters.

Pollsters say undecided voters and Peruvians living abroad could tip the balance in the crunch poll.

Overseas Peruvians make up around one million, almost 4%, of the 25 million-strong electoral roll. Normally few of them vote – only 0.8% in the first round of the election in April, when COVID-19 lockdowns were commonplace.

However, the head of Peru's National Office of Electoral Processes, Piero Corvetto, said that with vaccination programs now further advanced in areas where Peruvian expatriates predominate - such as the United States, Spain, Argentina and Chile - more people were likely to turn out.

He said he expects overseas Peruvians to account for 1.5% of the vote.

A neck-and-neck result could lead to days of uncertainty and tension if it takes time to settle on a winner.

Fujimori, who lost the 2016 election by just 40,000 votes, has said it was a mistake for her not to ask for a recount.

Castillo has said that if something untoward were to happen, he will "be the first to summon the people," although on Saturday night, he told the crowd he would respect the electoral results.

Some 160,000 police and soldiers have been deployed to guarantee peace on election day.

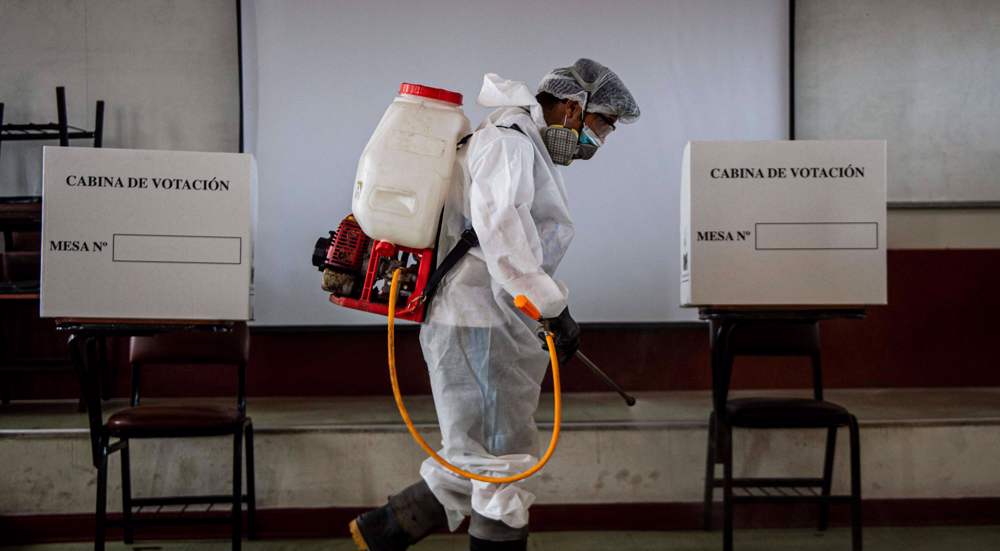

The 11,400 voting centers will open at 7:00 am (1200 GMT) for 12 hours.

The first results are expected at 11:00 pm on Sunday (0400 GMT Monday).

The new president will take office on July 28, replacing centrist interim leader Francisco Sagasti.

(Source: Agencies)

Palestinian resistance fighters hit Israeli Merkava 4 tanks

VIDEO | UK police brutal assault on Muslim family sparks outrage, protests

Hamas: Death of leader in Israeli jail amounts to murder

EU sends €1.5 billion to Ukraine from frozen Russian assets

VIDEO | Millions of Yemenis rally for Gaza, call for more anti-Israel operations

UN chief calls for Olympic truce as games begin in Paris

Paris Olympics begin as sports world reeling from loss of 400 Palestinian athletes in Gaza war

Iran warns ‘sworn enemies’, says sidekicks of US, Israel ‘displaced’ with bloody hands

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website