Discover Iran: Shahr-e Sukhteh, a Bronze Age marvel of urban planning, artistry and trade

By Ivan Kesic

- Acting as a pivotal hub along Bronze Age trade routes, Shahr-e Sukhteh hosted specialized workshops that transformed raw Afghan lapis lazuli into finished luxury goods, attesting to its central role in a vast long-distance trade network linking Mesopotamia with Central Asia.

- The city's exceptional preservation in the arid desert climate has yielded clear evidence of pioneering urban zoning, with distinct quarters for administration, industry, residence, and burial, illustrating an organized societal structure.

- The discovery of a prosthetic eye, crafted from a lightweight organic material with delicate golden threads, within a female burial dating to 2900-2800 BC represents the world's oldest known ocular prosthesis and reveals an astonishing level of early medical and artistic sophistication.

In the windswept deserts of southeastern Iran lies Shahr-e Sukhteh – the “Burnt City” – a silent metropolis whose extraordinary preservation and groundbreaking discoveries are transforming the understanding of early urban life and intercultural exchange at the dawn of civilization.

Situated on the arid fringes of the ancient Helmand River delta, the city stands as a monumental testament to human ingenuity in a demanding landscape.

Founded around 3200 BCE and flourishing for more than a millennium before its abandonment circa 1800 BCE, this vast mud-brick settlement marks the rise of one of eastern Iran’s first complex societies and continues to attract archeologists, historians and tourists.

Preserved by the region’s hyper-arid climate, Shahr-e Sukhteh offers a rare and remarkably intact window into a sophisticated urban experiment far removed from the better-documented civilizations of Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.

Its carefully delineated quarters, devoted to administration, industry, residence, and burial, reflect a pioneering approach to urban planning. Excavations have revealed striking evidence of technological innovation and artistic refinement, including early cranial surgery, the world’s oldest known artificial eye, finely painted ceramics, and a flourishing lapis lazuli industry.

As a vital hub along Bronze Age trade routes that crossed the Iranian plateau, the city functioned as a dynamic cultural and economic bridge, linking distant regions and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies that shaped the early Bronze Age world.

This feature explores Shahr-e Sukhteh’s transformative achievements, its distinctive place in prehistory, and its enduring significance as a cornerstone of our shared global heritage.

Crucible of urban innovation on the Iranian plateau

The rise of Shahr-e Sukhteh coincided with a transformative era in which scattered village communities across the Iranian plateau gradually coalesced into more complex, urban societies.

Strategically positioned at the crossroads of overland trade routes, the city linked Mesopotamia and the Iranian highlands with the Indus Valley, Central Asia, and Afghanistan, anchoring it within a vast intercultural network.

Founded around 3200 BCE, Shahr-e Sukhteh belongs firmly to the Proto-Elamite horizon, a constellation of settlements sharing administrative and cultural traits, confirmed by the discovery of a Proto-Elamite tablet at the site.

Unlike the romanticized image of civilizations flourishing in fertile river valleys, this city embodied a different model: one that adapted to a harsher environment and prospered through trade, craft specialization, and economic connectivity.

Pioneering urban planning: A city of distinct quarters

What distinguishes Shahr-e Sukhteh from many of its contemporaries is its strikingly advanced urban organization, an early and sophisticated experiment in planned city life.

Rather than developing as a random cluster of buildings, it was deliberately divided into clearly defined functional zones.

Excavations have uncovered a monumental northwestern quarter containing substantial administrative or religious structures with walls exceeding one meter in thickness.

To the east lay a residential district of courtyard houses arranged along narrow alleyways, incorporating dedicated spaces for living, cooking, and craft production.

Equally significant were the specialized industrial sectors: a northwestern lapidary quarter devoted to stoneworking, particularly lapis lazuli, and a southern zone focused on flint tool manufacture.

This purposeful separation of ceremonial, residential, and industrial spaces, alongside a vast and distinct cemetery, reveals a highly organized society with a nuanced understanding of urban functionality, economic management, and social structure.

Industrial engine: Mastery in stone and precious materials

The industrial quarters of Shahr-e Sukhteh formed the economic core of the city, demonstrating a remarkable level of technological specialization that sustained its prosperity and extensive trade connections. Artisans excelled particularly in working semi-precious stones.

Workshops in the northwestern sector reveal extensive evidence of lapis lazuli processing, a vivid blue stone imported from Badakhshan in modern Afghanistan.

Craftsmen skillfully transformed raw material into beads and other objects. The discovery of semi-finished items identical to those at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in Mesopotamia indicates that Shahr-e Sukhteh served as a central processing and distribution hub, supplying Sumerian elites.

Beyond lapis, artisans produced objects from agate, turquoise, chalcedony, and flint, alongside evidence of advanced copper metallurgy. This concentration of specialized craft production on an industrial scale reflects a sophisticated economic system with labor division and access to far-reaching trade networks.

Canvas of clay: Artistic expression in pottery and figurines

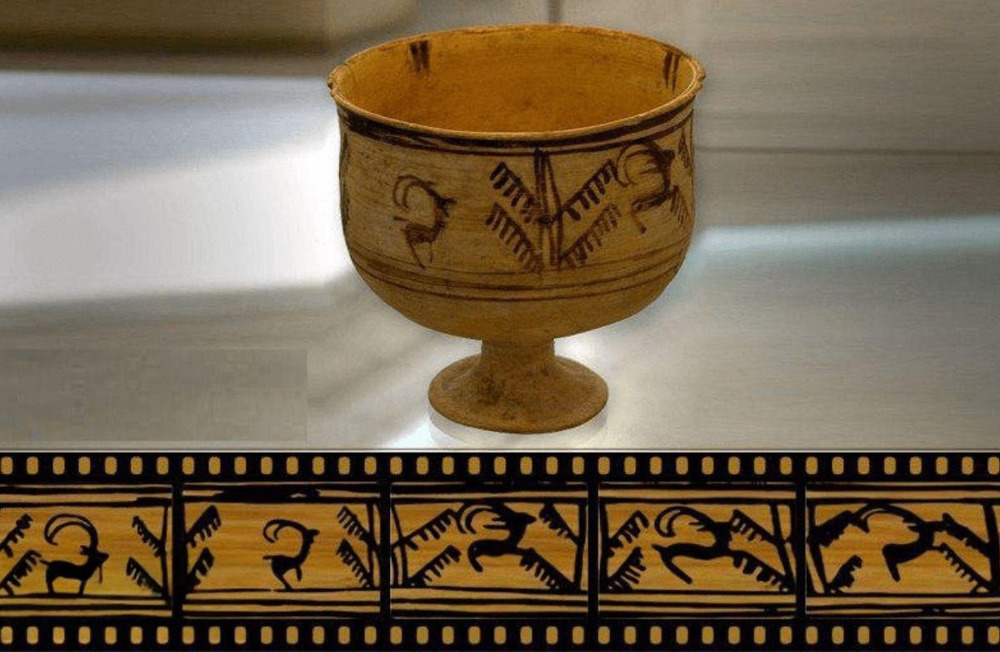

Shahr-e Sukhteh’s artistic output offers a vivid window into its inhabitants’ aesthetics and daily life. The city produced diverse pottery forms, decorated in styles linking Central Asia and Baluchestan, highlighting its role as a cultural crossroads. Some vessels featured sequential patterns that animated when rotated, showcasing playful and sophisticated artistry.

Thousands of clay and terracotta human and animal figurines have been uncovered across the site, from homes to monumental structures. These figurines, stylistically tied to Central Asia and Baluchistan, likely served ritual or votive functions, reflecting a shared yet locally distinct symbolic language across the eastern Iranian plateau.

Silent testimony of the graveyard: A window into life and death

The expansive cemetery of Shahr-e Sukhteh, estimated to hold between 20,000 and 37,000 graves, provides an unparalleled window into the city’s social hierarchy, health, and belief systems.

Burial types range from simple pits to elaborate catacombs, with richly furnished tombs likely belonging to elites or tribal leaders.

Grave goods are remarkably diverse and well-preserved, including intricate baskets, wooden vessels, alabaster objects, metal seals, and even a wooden game board with pieces.

Biological remains have revealed advanced medical knowledge, such as a skull showing surgical treatment for hydrocephalus.

Most famously, the burial of a tall woman (c. 2900–2800 BCE) contained the world’s oldest known prosthetic eye – a lightweight organic object with delicate gold threads mimicking radiating capillaries.

Nexus of Bronze Age exchange: Significance for world heritage

Shahr-e Sukhteh’s global significance lies in its profound interconnectedness. The city was a central hub in third-millennium BCE interaction networks.

Its material culture – from Proto-Elamite administrative tools to Central Asian-style pottery and lapis lazuli destined for Mesopotamia – places it at the heart of a trade and cultural web spanning the Euphrates to the Indus.

The site bears exceptional testimony to a civilization that served as a cultural conduit, facilitating both trade and the exchange of ideas, technologies, and artistic motifs. While the full scale of long-distance commerce continues to be studied, the presence of foreign goods and stylistic influences is indisputable.

Shahr-e Sukhteh demonstrates how early urban centers in seemingly peripheral regions were crucial in weaving together the economic, technological, and cultural fabric of the ancient world.

Adaptation and abandonment: the legacy of the Burnt City

The ultimate fate of Shahr-e Sukhteh is as revealing as its rise. The city was not destroyed in a sudden invasion but gradually abandoned over centuries, likely due to environmental shifts.

Changes in the Helmand River’s course, compounded by broader climate fluctuations, transformed the once-fertile delta into the arid landscape seen today.

Archaeological evidence shows the city shrinking over time, with open spaces expanding until only a single large building remained occupied. This pattern indicates a gradual, adaptive response to ecological pressures rather than catastrophic collapse.

The population likely dispersed to smaller, more sustainable villages following water sources. This story of human adaptation to environmental change resonates with contemporary global concerns, positioning Shahr-e Sukhteh as more than a relic. It is a case study in the long-term relationship between civilization and climate.

Pillar of human history and an invitation for the future

Shahr-e Sukhteh stands as a cornerstone of humanity’s collective past. Its exceptional preservation provides a nearly unparalleled laboratory for studying the transition from rural settlements to complex urban societies in eastern Iran.

The city’s artistic and technological achievements, from early ophthalmology to international trade, challenge simplistic narratives about the origins of civilization. Its planned layout, industrial specialization, and expansive necropolis reveal a highly organized proto-historic society.

As a UNESCO World Heritage site, its protection and ongoing study are vital. Each excavation and scientific analysis continues to illuminate the networks that connected the ancient world, demonstrating that even five millennia ago, innovation and culture flourished through exchange, and human societies were deeply interconnected across vast distances.

Shahr-e Sukhteh is not merely a silent ruin; it is a vibrant echo from the dawn of urbanization, urging us to look beyond traditional centers and recognize the intricate, networked tapestry of our shared human heritage.

Nine Palestinians killed in Israeli strikes across Gaza Strip despite ceasefire

Syria's HTS says Israeli regime 'seeking conflict' in region

Gunmen kill at least 32 people in northern Nigeria

Israel attacks south Lebanon amid ongoing ceasefire violations

Discover Iran: Shahr-e Sukhteh, a Bronze Age marvel of urban planning, artistry and trade

VIDEO | Thousands march against NATO summit in Munich

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Child detentions surge under Trump deportation campaign: Report

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website