How aromatic resin from Iran is captivating global fragrance markets

Global trade dynamics increasingly favor specialized, high-value natural products over bulk commodities, especially in emerging economies striving to diversify export bases amid geopolitical uncertainty.

Iran, historically dependent on hydrocarbons, is exploring alternative revenue sources that capitalize on its rich biodiversity and traditional knowledge.

One such opportunity lies in medicinal and aromatic plants, whose global demand is growing alongside consumer preferences for natural ingredients.

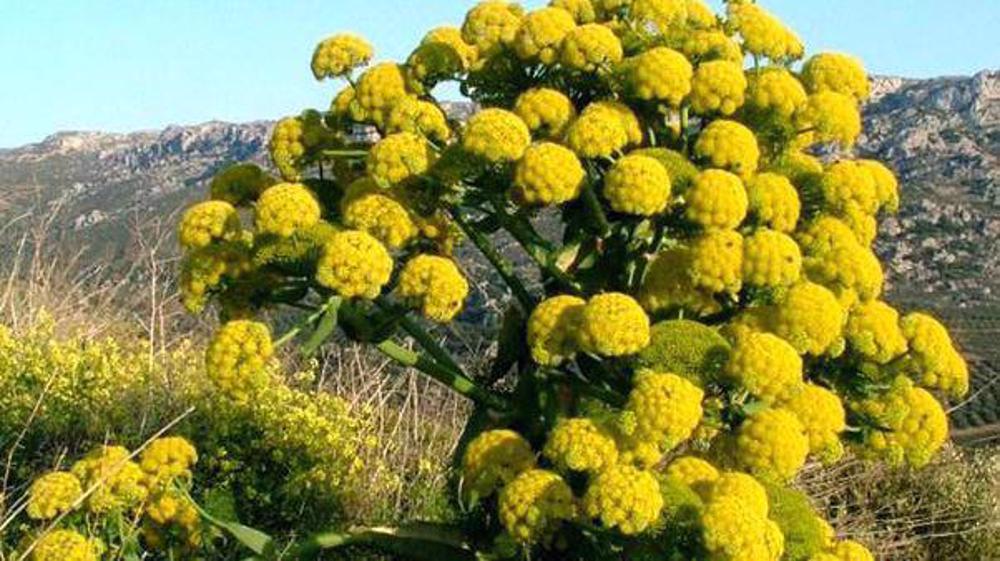

Among these plants, barijeh—a resin-producing species native to Iran—is gaining attention for its potential to support rural communities, encourage sustainable farming practices, and expand Iran’s footprint in international markets.

Barijeh, known scientifically as Ferula gummosa, produces a resin called galbanum gum. This sticky substance has long been used in Persian medicine for its anti-inflammatory properties, but today it draws the interest of international buyers more for its aromatic qualities.

In particular, barijeh resin is prized in the global perfume industry as a natural fixative—a component that stabilizes and extends the life of fragrances.

The harvesting process is meticulous. During late spring, workers make careful crescent-shaped incisions in the root crown of mature plants. A milky sap seeps out, hardening over days into a golden gum, which is then collected by hand.

Though the quantities harvested are modest, the resin commands premium prices in European luxury fragrance markets. Essential oils distilled from barijeh resin can fetch thousands of dollars per liter, with Iranian oil noted for its superior chemical profile.

Global demand for natural and organic products, especially in cosmetics, food, and wellness sectors, has created a strong market for essential oils and plant resins.

Barijeh fits neatly into this niche, benefiting from rising consumer preferences for eco-friendly and traditionally sourced ingredients.

In the northern province of North Khorasan, particularly around Shirvan and Esfarayen, barijeh cultivation is moving away from wild collection toward managed farming. This transition is critical for sustainable production and the preservation of local ecosystems.

Unlike many agricultural crops, barijeh requires a patient approach. The plants take four to five years to mature enough to produce harvestable resin.

Overharvesting or premature tapping can damage the plants and diminish yields, so farmers adopt careful, long-term management practices.

Once harvested, the resin is cleaned and sorted before being sent to distillation centers in cities such as Mashhad and Tehran, where it is processed into essential oils for export.

While the artisanal methods of collection and processing limit large-scale production, they help maintain the high quality and purity that discerning international buyers demand.

According to Iran’s Ministry of Agriculture, North Khorasan alone has over 1,285 hectares devoted to medicinal plants, including barijeh.

The province produces nearly 2,000 tonnes of these plants annually, with barijeh now the leading export among them.

It has outpaced other valuable range plants like katira (tragacanth gum), ushaa, and anguzeh (asafetida), which together account for 15 to 20 tonnes exported yearly to European countries.

Barijeh resin is exported primarily to Germany, France, Italy, and Austria. While the raw resin brings in an estimated 200 billion rials (about $4 million) annually, processing it domestically could multiply its value by up to 100 times.

This points to a significant opportunity for further development within Iran’s natural products sector.

Beyond its economic value, barijeh cultivation supports environmental sustainability. The plant thrives in marginal, drought-prone areas unsuitable for intensive agriculture.

Its deep root system helps reduce soil erosion, stabilize slopes, and maintain soil fertility naturally, without the need for synthetic fertilizers. This makes barijeh an ideal crop for regions facing water scarcity and challenging farming conditions.

Socially, barijeh cultivation and processing provide important livelihood options in rural areas. Seasonal work related to harvesting, cleaning, and packaging offers employment opportunities in regions where youth migration to cities is common and industrial jobs are scarce.

Women’s participation in these post-harvest activities, though often informal, plays a crucial role in income generation and community development.

Barijeh’s emergence as a key export crop illustrates how Iran’s non-oil economic strategy is increasingly tapping into its unique biodiversity and centuries-old traditional practices.

By focusing on niche agricultural products with high market value, the country is creating new avenues for rural prosperity and economic resilience.

The journey of barijeh—from the sun-baked soils of Iran’s northeast to the perfume ateliers of Europe—is a story of tradition meeting modern global markets.

It highlights the potential for natural, sustainably harvested products to contribute meaningfully to both local economies and international trade.

In short, Iran’s barijeh stands as a symbol of how native resources, cultivated with care and knowledge, can carve out a distinctive place in global markets.

UK ‘preemptively’ discharges pro-Palestine hunger strikers recovering in hospital

US dollar falls in Iran amid rising export currency supply

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ for Gaza an extension of Israeli occupation: Ex-UN rights chief

IMF expects Iran’s economy to grow by 1.1% in 2026

Over 9,350 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons as of early January: Rights groups

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Israel plans to seize Palestinian-owned land in occupied East al-Quds

VIDEO | Displacement in Al-Ouja: A broader push to reshape the occupied West Bank

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website