How to read N Korea-US politics: A secular row

By M. Amirisefat

Over the weekend, North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un has announced plans to stop the country's nuclear and missile tests and close a nuclear test site. The news comes at a time which seems the Communist nation is overhauling its foreign policy and changing its rhetoric on a vast number of issues, including its missile program, denuclearization and a change in anti-US policy.

In line with the sudden change, North Korea's leader has announced plans to stop the country's nuclear and missile tests and even has gone as far to close a nuclear test site.

"From April 21, North Korea will stop nuclear tests and launches of intercontinental ballistic missiles," South Korea's Yonhap news agency quoted North Korean state media as saying on Saturday.

The Americans have also been optimistic about the new atmosphere and change of tone. US President Donald Trump abruptly admitted that CIA Director Mike Pompeo made a secret visit to Pyongyang over the Easter weekend and held talks with Kim. He also hailed Pyongyang’s decision to potentially stop its missile program, tweeting on Friday that "North Korea has agreed to suspend all Nuclear Tests and close up a major test site. This is very good news for North Korea and the World - big progress! Look forward to our Summit."

Before all this, Trump had said yes to Kim Jong-un’s suggestions to meet in person and in a startling U-turn from his threat of war against the North declared that “we hope to see the day when the whole Korean Peninsula can live together in safety, prosperity and peace.”

But besides the assorted colorful headlines one hears and reads everyday and in addition to the speculations, rumors and various pieces of analysis about such a development, I contend one should pay careful attention to the underlying forces that shape such changes. Those forces, as British-Russian political philosopher and historian of thought Isaiah Berlin has taught us, are usually a product of “ideas” and their power:

'Over a hundred years ago, the German poet Heine warned the French not to underestimate the power of ideas: philosophical concepts nurtured in the stillness of a professor's study could destroy a civilization' - Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty, 1958.

Of course the opposite is also true. Ideas can determine the levels of conflict among peoples and civilizations and could contribute to lower levels of conflict and animosity.

Communism and Liberalism’s common roots

Both the West and a variety of Communist nations have overtime managed to steer clear of their conflicts becoming existence-threatening. This is not a claim confined to the North-US conflict, but has been a historical fact. At the height of the Cold War, the Americans and the USSR still negotiated over vital issues, and even the most dangerous episode of the Cold War – The Cuban missile crisis – was somehow resolved without leading the two countries into a full-scale nuclear war that could have potentially destroyed human civilization.

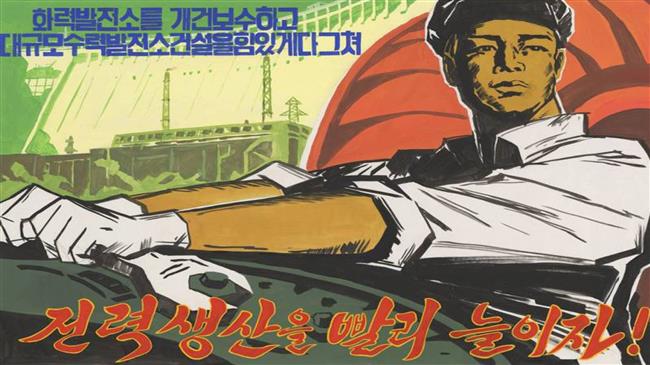

The key ideologies of the twentieth-century -- Liberalism, Communism and for a shorter period of time, Fascism -- were all the children of secular modernity which had renounced the entirety of celestial or divine authority. Liberalism and Communism both had one major aim: the creation of a better and more prosperous human condition in “this world,” not the other.

Liberalism and Communism had the same goals and aims, but deployed fundamentally different means to such utopia. Liberalism advocated free market mechanisms in the realm of economics, and democracy as form of government in the realm of politics. Communism deployed state-controlled economics, and influenced by Marxism’s concept of “the dictatorship of the proletariat,” the rule of the Communist Party was its preferred form of running politics.

Even though the means of attaining economic prosperity and political tranquility were different between the two rival camps, both systems claimed a steadfast faith to secular/instrumental rationality. The difference was the outcome of such rationality, not the adherence to such rationality disconnected from all sorts of transcendental sources, including religion.

This is why prominent political philosopher Leo Strauss clearly states that communism and liberal democracy both originated with the dawn of modernity in post-middle age Europe, thus had common roots, although departing in paths.

N Korea-US tensions: Dispute inside a shared paradigm

Such common roots and an unwavering belief in the autonomy of the human being as the sole source of power and change seem to have translated itself into a different rivalry among the two secular rival brethren than, for instance, compared with the West’s challenges in the Middle East with Fundamentalist groups and factions that resort to metaphysical/religious sources as their modus operendi.

American confrontation with nations seen as belligerent, but adhering to secular narratives of world affairs and politics, such as the former USSR and the eastern bloc, or contemporary Venezuela and North Korea, pose far less fundamental challenges for Washington than dealing with a group like the Taliban or a government based on meta-physical principles. This is probably why the doctrines of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) worked between the Soviet Union and the US, or political and economic pressures coupled with aggressive negotiations, and of course Cuban “rational” calculations ultimately translated to a relative calm in relations and the opening of the US embassy in Havana in 2015. The same is true about tensions between Western allies and other Eastern-bloc pro-Soviet states, even the most belligerent ones such as General Tito of Yugoslavia.

The above scenarios of appeasement, pressure or mutual destruction as guarantees of peace among hostile nations are much less probable to work with a group like the Taliban or terrorist entities fighting against the central government in Syria.

In the case of North Korea, like the other cases mentioned where nations adhered to conventional secular modes of conduct, Washington and Pyongyang are walking along the same lines that we have seen before when two contrasting products of secular politics decide to end tensions.

Korea might claim it has achieved nuclear competence, and the US might claim it has destroyed the North’s economic infrastructure, hence argue that time is ripe for negotiations, but at the end of the day the most salient issue among the warring sides is their interest to enter a process of conflict-resolution based on mutual benefits that logical actors without non-secular considerations can assess and calculate.

In this sense, though the North Korean threat to the US might seem grave and Washington’s crippling sanctions and aggressive regime-change policy might seem existentially threatening to the North, both belligerent camps are inside the paradigm of modern secular international relations and adhere to secular ideologies that have historically illustrated although they might drag the other to the brink of war, but usually stop before full-blown combat due to the calculations of the modern secular mind that is usually risk averse, or least attempts to be risk-averse.

A recognizable row

In this regard, the North Korean-American debacle is a challenge like all other challenges of recent years among a hegemonic power (US) and its conventional secular rivals. Sooner or later, the two sides will meet and ideology will stop in favor of rational pragmatism, as it has in previous and harder cases, like the tensions between the US-led Western bloc and the Soviet-led Eastern bloc that shaped the entirety of international relations for more than 70-years. One might challenge this conclusion with examples of how Fascism, the third child of 20th century modernity, almost destroyed human civilization without a revert to rational conflict-solving strategies. This is a reasonable challenge to a theory of conflict-resolution among secular rivals and could be the subject of a separate article.

For the sake of brevity, a short response could be that in a unipolar world where US hegemony shapes many of the mechanisms and interactions in the current international system of power, and where MAD encourages even more calculations before the initiation of a conflict among major powers in the system, pre-WWII political relations and considerations, which were a prelude to the Nazi plague, are no longer in place. One could cautiously claim the post-WWII era is thus a significantly less threatening era than other eras of international relations where full-scale wars among powerful players were common currency.

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Syrians boycott electricity bills after 800% hike

VIDEO | Domestic breakthroughs place Iran In laser leadership

Trump threatens Iraq over ex-PM Maliki’s return

VIDEO | Tehran tax administration building destroyed in organized arson, explosion

National unity will block threats to Iran’s territorial integrity: Intelligence minister

VIDEO | Israel-US scheme for Gaza

VIDEO | Iraqi parliament delays vote to elect new president

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website